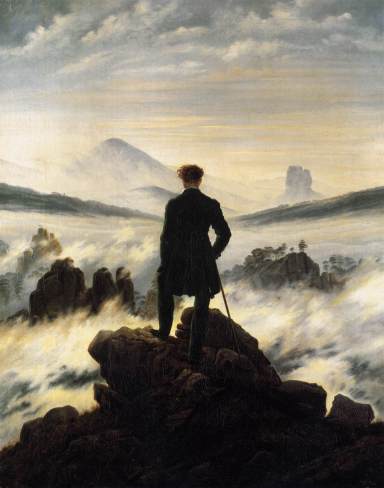

“The Monk by the Sea” (“Der Moench am Meer”)

The Monk is back.

Two of the most famous paintings from Germany’s Romantic period are back on display at a central Berlin museum after a two-year restoration. I recently visited that exibition and appreciated the famed landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich. The making of a perfect piece of art has always been a purification process of the artists soul. Especially in Romanticism, in which artworks supposedly not only depict an object, but represent holistic the artists inner side: artwork and artist converge in the Ego. As defined by C.G. Jung, probably not the Ego alone, but the personal and collective Unconscisiousness and finally the Self. When the Artist finished his work, he knew that gods and humans alike would feel pleasure when they see the painting.

True. Crowds clustered araound the paintings “The Monk by the Sea” (“Der Moench am Meer”) and “The Abbey in the Oakwood” (“Abtei im Eichenwald”), which were created as a composite work. Investigation of nature, incorporated always proportion, harmony, and unity. Similarly, in his Metaphysics, Aristotle found that the universal elements of beauty were order, symmetry, and definiteness. That was clearly revived in Caspar David Friedrich’s art. What is perhaps the most famous Caspar David Friedrich,”Monk by the Sea”, was completed in 1810, and is large-scale oil paintings in landscape mode 175 x 110 cm. That painting the Monk by the Sea (Der Moench am Meer) has an impressive usage of line and space, but also “uniformity and boundlessness”, as Heinrich von Kleist once remarked: “Nothing can be sadder and more uncomfortable than this position in the world: the only spark of life in the vast realm of the dead the lone center shared circle the picture, with its two or three mysterious objects like an the apocalypse, as if it had Edward Young’ Night Thoughts. And, since it in its uniformity and boundlessness it has nothing but the frame in the foreground“. This sentence was written by the poet Heinrich von Kleist one year before his suicide in an review of this painting “Monk by the Sea”.

Psychoanalytic interpretation

In my humble opinion, this painting of the central Berlin Alte Nationalgalerie on Berlin’s Museum Island, is also a showcase, both for photography and psychoanalytic interpretation. Where are your leading lines directing you? Well – to infinity. There is only on vertical in this painting, that is, that silhouette of the monk. In fact, so I reaffirm this psychoanalytic formulation, the painting has something visionary. It offers an insurmountable simplicity in the composition. Three horizontal zones divide the painting: the sky with raspberry mist, black sea and almost white sand, each delimited by the yank edge and the horizon. The only vertical line is the monk, a point, a human counterpart to the vastness of nature – in the void. Exceptional the human: Upright and defenseless.

“The Monk by the Sea” (“Der Moench am Meer”) Caspar David Friedrich

In his painting, Friedrich steps over all valid rules of landscape painting or a landscape photography, more radical than ever before. There is now nothing more to see. The creation has no perspective, no depth anymore, the narrow dunes shore is just a whitish stripe, that rises at an obtuse angle to the left and from the apex. By the monk, the only vertical line, the dunes shore decreases to the left. In a traditional landscape, the foreground is kept dark, only in the middle distance, the colors are lightened up. Exposed on the horizon, abruptly drawn as with a ruler, and extremely low in between the narrow dark strip of water, is actually: nothing

This is because the image is composed almost entirely of heaven. Up to the horizon line one can find some orientation, because there are still proportions visible, especially the monk.

He represents something like a scale, but embodying the background no proportion can any longer be detected

The background clearly represents the non-measurable, the unconsciousness, the spirituality in nature. This refers to the shoreline because the sky seals over the deep blue in a way that the shoreline is mirrored at the height of the monk figure. All lines literally flee like rays, from the middle of the painting and also the blue awakens the illusion of depth. An impression of bright clouds just above the monk separates the horizon line sharply and creates two zones. The land-maritime zone ínteracts like one, single surface starting at horizon.

The monk vertainly represents Friedrich himself, according to the romantic ideal that every art has to show the inner form of the artist – paintng and artist are the same. Or on other words, the artist paints, what he sees in himself. No wonder, das this art can be easily related to C.G. Jungs concept of our inner world.

Lines

From the worn out “rule of a third” in photography composition, only the horizontal division is viable: pre-foreground, middle ground, background. Each is associated with a natural element: Air, Water, Earth. Drastically, the sky occupies five sixth of the image. Any limiting scenes, like rocks, shrubs, trees or a main motive to frame and highlight is missing. Only the wooden frame limits the image content. This creates openness to all sides and the impression of virtual infinity. As an infrared photograph has shown, Caspar David Friedrich painted over two ships, in the interests of this elementary space and line experience. The deliberately thoughtful, geometric composition of the painting receives its special emphasis through two successful Invasions: The monk is placed by the painter on a little promontory, which protrudes into the sea, like lighthouse. Geometrically his horizontal position conforms to in Golden Ratio , which – in accordance with a classical Cartesian theory of proportions was the harmony ideal of Greek art. The golden ratio (“sectio aurea”) is the division of a straight line in two uneven portions such that the entire route to greater leg behaves like the greater part of the route smaller leg.

This golden ratio, also known as the divine proportion, golden mean, or golden section, is a number often encountered when taking the ratios of distances in simple geometric figures such as the pentagon, pentagram, decagon and dodecahedron. In mathematics, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities or: a+b to a as a is to b. The figure on the right illustrates the geometric relationship. This image outlines generated more excitement than the central axis. If you follow the shore line, one ends on the horizon, the other on th border of the clouds and blue sky.

Colors

There are no contrasting colors, which stand out significantly from one another, dominate the picture, but an uniform gray tone with flowing transitions. The image is designed tone on tone. Whitish-brownish extends the sandy beach. Leaden grayish, to almost black surging water. Variations of blue and gray piles up the sky. It gives a gloomy, uneasy feeling, very much the opposite of the light in French impressionism. Well, it is the North Sea with dark water, in pale, melancholical light.

“The Monk by the Sea” (“Der Moench am Meer”) – cut

The land lacks any vegetation, just a barren soil. The blowing of the wind and the noise of waves and a cold breath of unconsciousness seems to meet us. The monk looks vulnerable and lost with himself and the infinity. Although small and fragile, he is not meaningless, because he is the only living creature, aware of the situation, the only vertical in a structure of horizontal. No object no without observer. The Monk represents the opposite of infinity – mortality and consciousness.

Symbolism

The Abbey in the Oakwood

The Abbey in the Oakwood (German: Abtei im Eichwald) is the oil painting by Caspar David Friedrich adjecent to the “Monk by the Sea. It was painted between 1809 and 1810 in Dresden. The ruin is again the golden ratio; the dead trees rise up to the sky.

The Western Monasticism is often not characterizes by contemplatives alone (except strict orders) like Sufism. Benedikt von Nursia, the father of Western Monasticism created that proverbial: “Ora et labora”, pray and work. In other words, following Max Weber’s great sociological-religious studies, rationality and spirituality merge.

Caspar David Friedrich’s painting “Monk by the Sea” has psychological content. It represents the existential fundamental loneliness of man in the universe. A modern, a worldly symbol of the finite ego as guest of the infinite. Both literally and figuratively located in one the “border situation” on the Land border and in the face of centreless limits. It is increasingly strengthened and reaches finally this extreme situation, which may, as C. G. Jung believed, to be the point, at which the collective unconscious opens to an “ubiquitous continuum That continuum represents “an unextended omnipresence” or the “death of the ego”. The picture shows in a metaphysical sense the minor role of the ego, the individual against collective archetypes of the unconsciousness.He also suggested that finding the Self is like a marriage which becomes rarely or perhaps never smoothly and without crises a personal relationship; “There is no consciousness without pain”. The first step to the individuality is the

break off with the unconsciousness of the herd. “It is the loneliness of mature man, who no longer ´depends on the value judgements of his environment, but in his relationship to the Self is firmly established.”

Like in another of my favorite painting of him: “The wanderer above the mist”. Both, “The “monk” in landscape mode and “The wanderer” in portrait orientation show the same basic human condition, in complementary settings, sea and mountains. The theme of the solitary wanderer and his longing for primeval nature is a common one in German Romantic literature. But Caspar David Friedrich sought to express in painting his own mystical or pantheistic view of nature. “The divine is everywhere,” he once wrote, “even in a grain of sand.” He was lonely, a serious and solitary figure, who spent most of his life alone, painting the countryside of his beloved Germany. His mysterious and haunting landscapes expressed not only a love of nature, but also an intense inner world.

Conclusion

To me, Friedrich had a truly unique style; he could transform landscapes from a mere forest to a wooded wonderland where each branch symbolized something greater, something deeper. He was an early symbolist, to early for him. His trees were no longer just trees, but beautiful wooden creatures that represented the German strength or the longing for transcendence. The rays of the sun didn’t just serve to illuminate the ground but to show the light of heaven.

Unfortunately, reception of Friedrich’s work deteriorated as he aged. Eventually even his patrons lost interest. Friedrich died while his art was no longer wanted. Critics thought it too personal to understand, completely disregarding what made the work so original in the first place.

However, his works were regarded highly later, by Symbolist and Surrealist artists, such as Max Ernst. The time took note of the allegorical meanings that saturated Friedrich’s canvases as a great source of inspiration and foundation. Carl Gustav Carus was a friend of Casper David Friedrich. Carus, a painter, nature philosopher and scientist, was seen by C.G. Jung as forerunner of psychoanalysis.

Another fascinating painting in this room: The Lonely Tree (German: Der einsame Baum). This is an 1822 oil-on-canvas painting also by German painter Caspar David Friedrich. The work depicts a panoramic view of a German landscape of plains with mountains in the background. A solitary oak tree dominates the foreground. Notice the broken, rotten top pointing to the sky. Despite the missing tree crown, the old tree still hangs on live visible by its green leafage. The roots, supposedly symbolizing the German people and their culture are firm and deep. The rotten top represents the German elite at that time, during the counterrevolution, 25 years before the tragically failed Revolution 1848. Just like today, a rotten, broken elite, but will the tree survive this time?Not with destroyed roots.

Friedrich loved encryption but coded his messages with clear symbols: The ancient tree, perhaps a German oak, is at the very center; at his feet is a swampy waterhole, a shepherd leaning on the tree and watching over his little flock. Behind, bathed in bright light, we can see a village surrounded by pastures, bushes and fields. Far in the background rises a steeple from behind the hills, the roofs of a city are visible. The city with its gothic church towers shall be read as metaphor for the Christian Middle Age. The painting is thus divided into a row of staggered, parallel planes, from the distant past to the present.

Friedrich influenced quite a few artists. It is no surprise, that among his admirers was another outstanding painter , the Norwegian Symbolist Edvard Munch, whose work has been explicitly related to Friedrich’s. Munch could identify with Friedrich’s symbolism and in one of his work a clear reference is seen to Friedrich’s “Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon” on the left.

Friedrich influenced quite a few artists. It is no surprise, that among his admirers was another outstanding painter , the Norwegian Symbolist Edvard Munch, whose work has been explicitly related to Friedrich’s. Munch could identify with Friedrich’s symbolism and in one of his work a clear reference is seen to Friedrich’s “Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon” on the left.

Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings tell a lot of the early nineteenth century, inspired by the French occupation and the Napoleonic Wars, the era of Metternichs Restoration, the connection between early nationalism, which was at that time a progessive, liberal movement.  The art historian Jens Christian Jensen attaches a clear political meaning to this work: his commitment to liberal political ideas of republicans, who were prosecuted as ‘demagogues’ and disturbance.

The art historian Jens Christian Jensen attaches a clear political meaning to this work: his commitment to liberal political ideas of republicans, who were prosecuted as ‘demagogues’ and disturbance.

Sources

Boime, Albert. Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848. University of Chicago Press, 2004

Jens Christian Jensen, Caspar David Friedrich – Leben und Werk, 1974. 10 Auflage 1995

Rüdiger Safrabski, Romantik eine deutsche Affäre, Hanser 2007

Kurt Kersten, Die Deutsche Revolution 1848-1849, Kassel 1055

You must be logged in to post a comment.